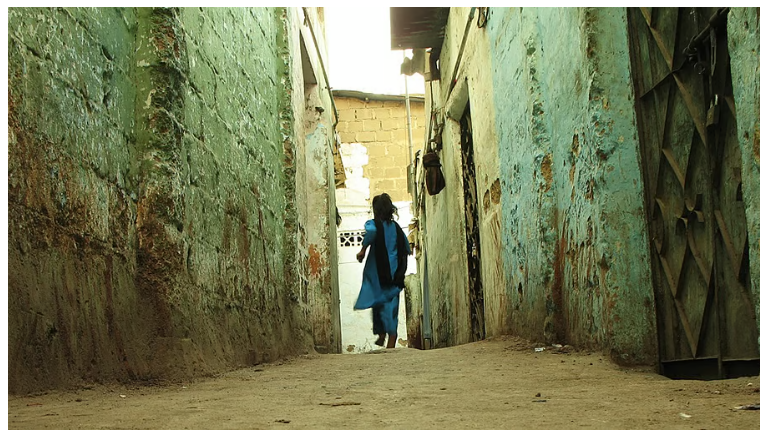

The call of the hour is to develop a child-responsive system to retrace and rescue missing and trafficked children — especially girls

Suhani (name changed to protect identity) was only 14. Married young and trafficked by her brother-in-law, the girl endured 23 harrowing days of confinement and sexual abuse. When her family approached the police, the initial response was disheartening—delayed, indifferent, almost dismissive. It took the persistent intervention of a local community-based organisation for law enforcement to act. Eventually, she was rescued, awarded compensation, and her perpetrator was convicted.

But her ordeal didn’t end with rescue or legal justice. Ostracised by her in-laws and pressured to withdraw the case, she stood her ground. With courage and quiet resolve, she resumed her education and found employment with a community-based organisation, determined to help others like her.

Suhani, however, is not an exception. She is just one of the many missing girls — some fortunate enough to return, most fading into data points or forgotten pleas.

Behind every missing child: A story of failure

The story of every missing child is layered — rooted in poverty, gender bias, child marriage, migration, and institutional apathy. While the reasons vary — elopement, trafficking, forced labour, or escape from abuse — the common denominator is systemic failure. From slow police response to weak inter-agency coordination, each disappearance reveals the cracks in our child protection apparatus.

As per the National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB) Crime in India 2022 report, there were 83,350 children reported missing, among whom 62,946 were girls (75 per cent), marking a distinct gendered scenario in such incidents. In other words, 3 of every 4 missing children in India are girls.

Trafficking thrives where protection falters

The COVID-19 pandemic deepened pre-existing vulnerabilities. Across the country, millions of families already burdened by poverty, found themselves cornered by desperation. Traffickers preyed on this desperation, luring parents with promises of jobs, education, or marriage for their children. Many girls were sent away — sometimes knowingly, often unknowingly — into cycles of exploitation.

Even when children are rescued, the trauma doesn’t end. Long absences, institutional delays, and lack of psychosocial support often lead to deep scars—physical, emotional, and social. Reintegration remains an uphill task.

What is being done—and what’s still missing

To address the crisis of missing and trafficked children, the government has introduced a range of measures. In response to a recent Lok Sabha question (Unstarred No. 4003, dated March 25, 2025), the Union Ministry of Home Affairs acknowledged the severity of the issue and highlighted several ongoing initiatives. These include strengthening Anti-Human Trafficking Units (AHTUs) across every district and establishing dedicated Women Help Desks at police stations throughout the country to ensure that initial complaints are received with sensitivity and prompt action.

A more coordinated data-sharing ecosystem is also being developed through the Crime Multi Agency Centre (Cri-MAC), a national-level communication platform designed to enable seamless online information exchange among law enforcement agencies. Parallelly, the Union Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) has operationalised Childline 1098—a 24×7 helpline for children in distress—along with ‘Railway Childlines’ to ensure protection at transit points.

MWCD is also running the TrackChild portal (with its citizen reporting feature Khoya-Paya) under Mission Vatsalya, aimed at tracing missing children with tech-enabled precision. To further streamline the rescue and rehabilitation processes, the ministry has issued a Standard Operating Protocol for all stakeholders including police personnel, child welfare committees, and juvenile justice boards.

Despite these initiatives, gaps in enforcement remain deeply troubling. Ground-level realities often reflect a persistent lack of coordination, delays in rescue efforts, and inadequate sensitivity in handling such cases. While the recently introduced Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) 2023 includes stringent provisions for kidnapping and trafficking, legal resolve alone cannot compensate for operational inertia.

What is still missing is the effective inter-agency collaboration and convergence, and empathetic engagement that this issue demands. Without these, policies risk remaining on paper, and children continue to fall through the cracks.

Prevention first: A community-centric response

Compensation and conviction, while important, are ultimately reactive measures. What’s urgently needed is a preventive, people-centred approach that addresses the vulnerabilities before a child goes missing. Prevention and early intervention must become the cornerstone of India’s child protection strategy.

This calls for activating local safety-net anchored by Village-Level Child Protection Committees (VLCPC) as the first line of redressal systems. Community members, teachers and members of school management committees must also be sensitised to track dropouts, especially in areas where child marriage or labour is prevalent. Anganwadi workers and Panchayati Raj institutions, given their proximity to families, should be trained to identify high-risk households and children who may be pushed into unsafe migration or coerced into leaving home.

VLCPCs can play a critical role in monitoring and intervening before a child falls off the radar. In addition, a coordinated effort by the police, social welfare departments, and local administration must help strengthen community surveillance systems. Tailored awareness campaigns that speak the language of the people, especially in vulnerable districts, are essential to shift attitudes and reduce stigma around reporting.

Only through this kind of decentralised, community-backed approach can India build a robust early-warning system—and make the first rescue happen before a child ever goes missing.

Time is running out for children

We must reframe the issue of missing children not as a policing matter alone, but as a child rights emergency. At stake is more than a number—it is the fundamental promise of protection, dignity, and justice for every child. This also demands behaviour change communication to address deeply entrenched social norms around gender, poverty, and education. To secure long-term gain, public engagement must accompany institutional reforms.

Our daughters, thousands of them across India, wait in silence — some for justice, others simply for a way home. Are we truly listening to them?

Article Credit: downtoearth